Byzantine Consensus: Oral Messages

This module describes a Byzantine consensus algorithm in which messages are not encrypted. An agent x that receives a message signed by an agent y cannot tell whether y signed the message or whether some other agent forged y's signature and corrupted the message.

This module describes solutions to the Byzantine problem with oral messages whereas the previous module studied the problem with written messages. For convenience we repeat the problem specification next.

An agent is a general or a lieutenant. An agent may be loyal or disloyal. Let \(N\) be the number of agents and \(t\) the number of disloyal agents. The general sends a command to each lieutenant where the command is either attack or retreat. A loyal general sends the same command to all lieutenants whereas a disloyal general may send different commands to different lieutenants. Each lieutenant decides to attack or retreat at the end of the algorithm.

If all loyal lieutenants get the same command then each loyal lieutenant obeys the commands that it received; if the command is attack then each loyal lieutenant attacks, and if the command is retreat then each loyal lieutenant retreats.

Even if loyal lieutenants receive different commands, all loyal lieutenants make the same the decision; either all loyal lieutenants attack or all loyal lieutenants retreat.

Notation

We use indices \(i, j, k\) for loyal agents; \(x, y\) for generic agents who may be loyal or disloyal; and \(e\) for disloyal agents. Nothing in an agent's id or data identifies the agent as loyal or disloyal. Moreover, the algorithm does not have to discover which agents act disloyally.For a nonempty list \(L\), we use the Python notation \(L_{*}\) to refer the last element of the list. For example, if \(L = [5, 6]\), then \(L_{*} = 6\).

For a list \(L\) and an element \(x\), the notation \(L , x\) represents a list consisting of \(x\) appended to the tail of \(L\). For example, if \(L\) is the list \([1, 2]\) then \(L , 3\) is the list \([1, 2, 3]\), and \(L, 3, 4\) is the list \([1, 2, 3, 4]\).

The general is the agent with index \(0\), and the lieutenants have indices \(1, \ldots, N-1\).

Let \(m[x]\) be the message that the general sends lieutenant \(x\), and let \(a[x]\) be the decision the lieutenant \(x\) makes.

Specification

The specification has two parts, validity and consensus.Validity: Loyal lieutenants obey a loyal general.

If all loyal lieutenants get the same message then each loyal lieutenant obeys the message that it receives.

\( (\forall i, j: m[i] = m[j]) \quad \Rightarrow \quad (\forall i: a[i] = m[i]) \)

Consensus: Loyal lieutenants make the same decision.

\( \forall i, j: a[i] = a[j] \)Assumptions

The oral Byzantine version makes fewer assumptions than the written version. The assumptions made are as follows:- Synchrony: The algorithm operates in a synchronous fashion in a sequence of rounds or synchronous steps. If an agent \(x\) does not send a message to an agent \(y\) in a given round then \(y\) can detect that \(x\) did not send a message to it in that round.

- Reliability: If an agent \(y\) sends a message \(m\) to an agent \(y\) in a given round then \(z\) receives \(m\) in that round.

- Receiver knows sender: An agent that receives a message knows which agent sent it. If an agent \(z\) receives a message \(m\) from an agent \(y\) in a round then \(z\) knows that \(y\) sent \(m\) in that round.

Why oral messages are harder

In the written version of the problem, if an agent \(z\) receives a message \(m\) from any agent where \(m\) is signed by the general then \(z\) knows that the general did send \(m\). An agent cannot forge the general's signature and send a false message. By contrast, in the oral, or unencrypted version, any agent can forge any agent's signature and send corrupted messages.Byzantine Generals Algorithm

Messages in the algorithm are either attack or retreat messages. If an agent \(x\) does not receive a message from an agent \(y\) on a round then \(x\) treats the absence of the message from \(y\) in the same way as if \(x\) received a retreat message from \(y\). So, the algorithm only deals with attack and retreat messages and does not deal with steps that an agent takes if it does not receive a message.First we describe the flow of message in the algorithm and then describe the algorithm

Message Flow

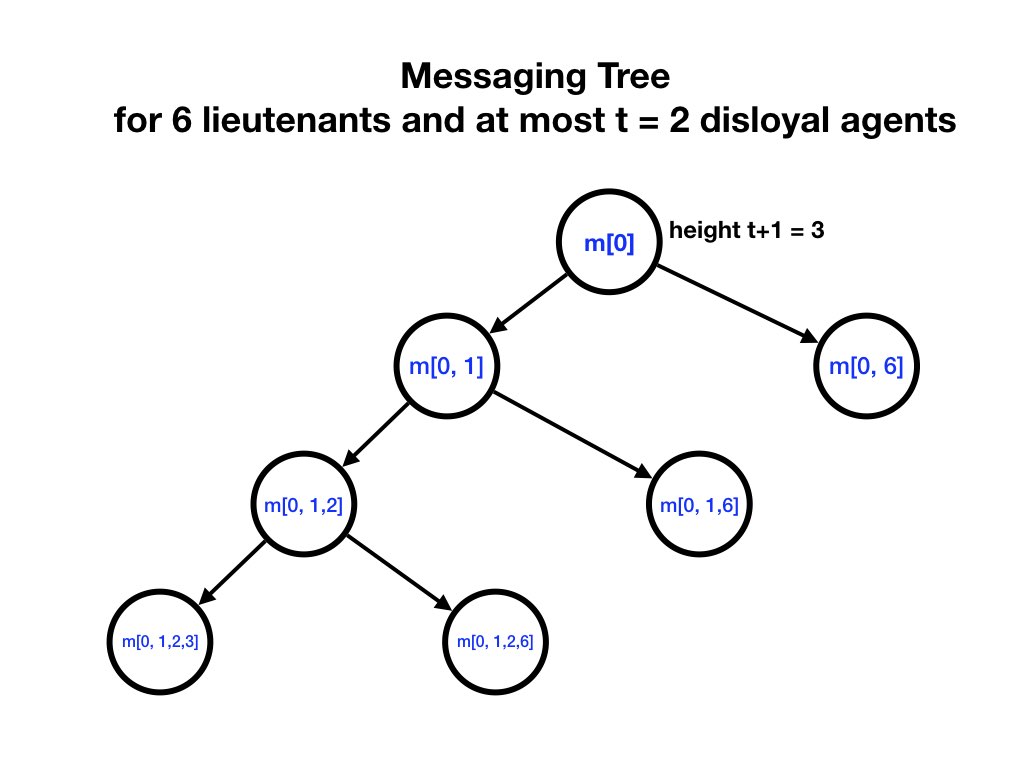

Messages flow along a tree of height \(t + 1\). The root node is \(m[0]\) which represents the general's command. Each node of the tree is of the form \(m[L]\) where \(L[0] = 0\) and \(L[1, \ldots, ]\) is a list of lieutenants where each lieutenant appears at most once.

The next figure illustrates a part of the messaging tree for \(N = 7,

t = 2\).

(There is insufficient space to show the complete tree.)

Each non-leaf node \(m[L]\) in the tree has a child \(m[L, x]\) for each lieutenant \(x\) that is not in \(L\). For example, \(m[0]\) has children \(m[0,1], m[0,2], \ldots, m[0, N-1]\).

\(m[0,x]\) is the message that lieutenant \(x\) receives from the general. \(m[0, x_{0}, \ldots, x_{k}]\) is the message that lieutenant \(x_{0}\) receives from the general and forwards to lieutenant \(x_{1}\), ... which in turn forwards the message to lieutenant \(x_{n-1}\), which in turn forwards the message to lieutenant \(x_{n}\).

If the general is loyal then it sends the same message to all lieutenants: \(m[0,x] = m[0]\) for all \(x\). Loyal lieutenants forward the messages that they receive; however, disloyal lieutenants may send arbitrary messages.

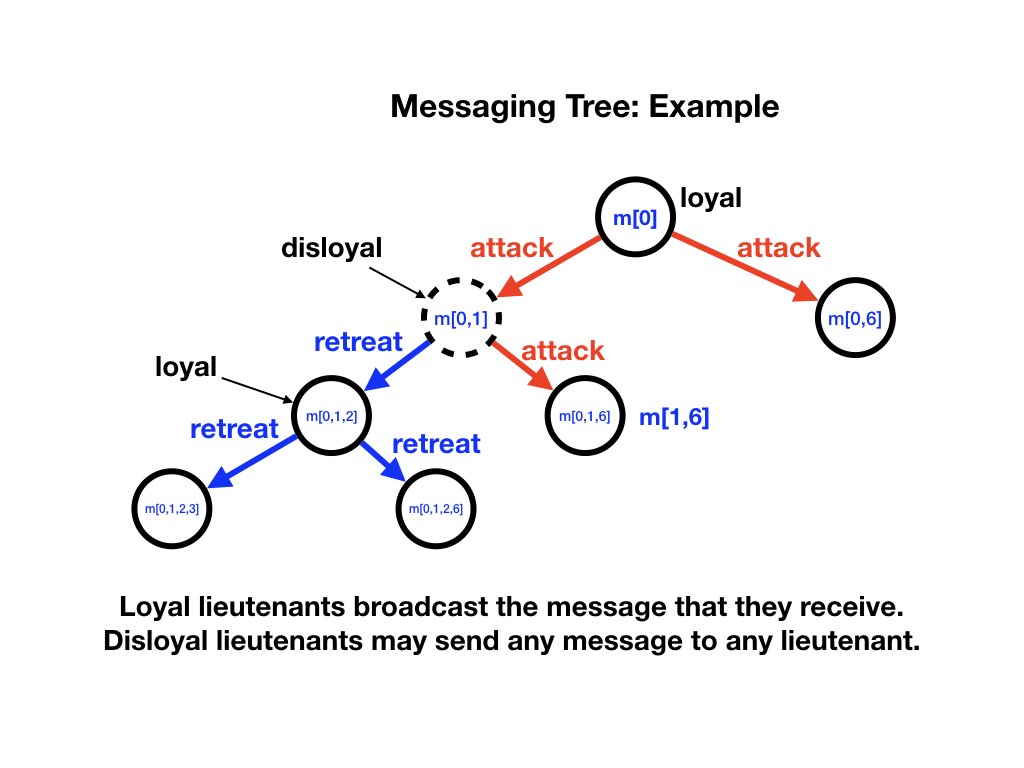

Example

The diagram below shows a situation in which the general is loyal and sends attack messages to all lieutenants. Lieutenant 1 is disloyal (shown as a dashed circle). Lieutenant 1 sends retreat messages to some lieutenants and attack messages to others. Lieutenant 2 is loyal, and so it broadcasts the message that it receives.

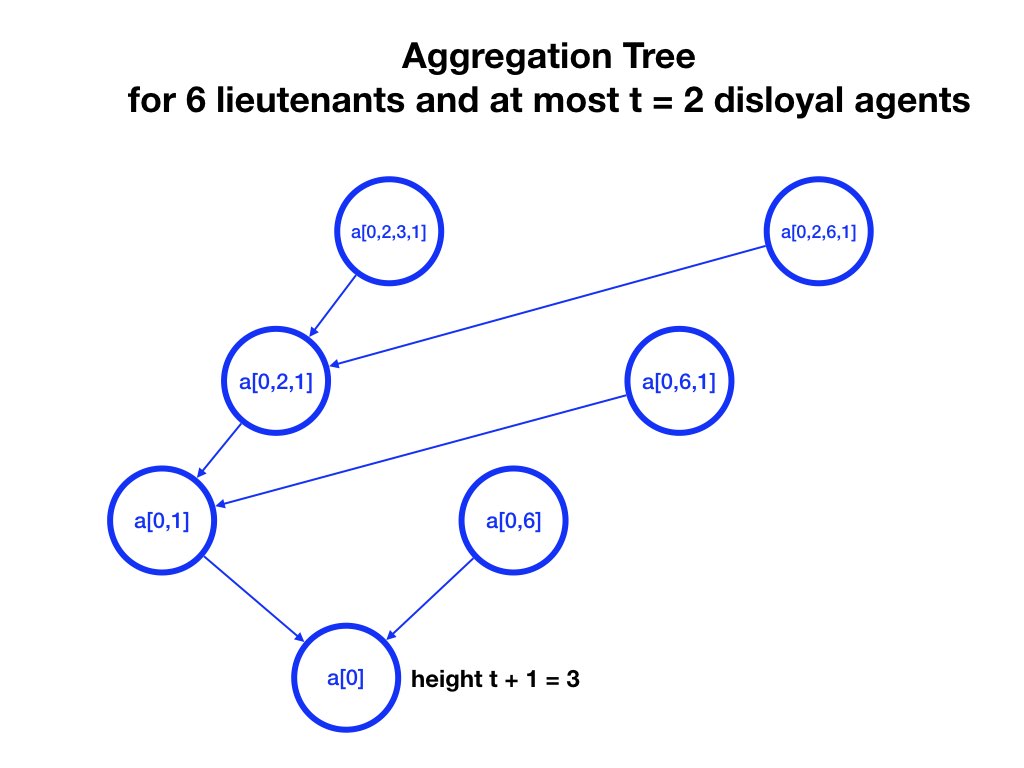

Aggregating Phase

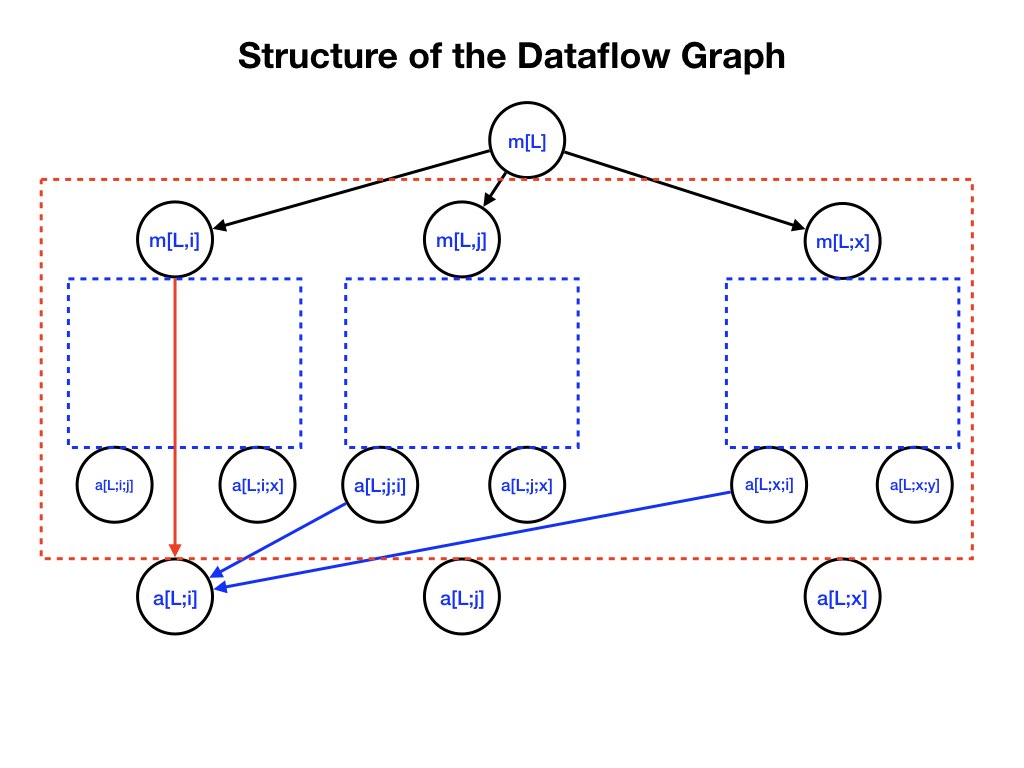

Messages received by a lieutenant are processed by the lieutenant in steps that are also represented by a tree called the aggregation tree. The aggregation tree has a node \(a[L]\) for each node \(m[L]\) of the message tree.

The diagram below shows a part of the aggregation tree for \(N=7,

t=2\); these are the processing steps of lieutenant 1.

Each node \(a[L, i]\) of the tree has a child \(a[L, x, i]\) for each \(x\) that is not in \([L, i]\). For example, \(a[0, 1]\) has children \(a[0, 2, 1], a[0, 3, 1], \ldots a[0, 6, 1]\).

Connections from Messaging to Aggregating Nodes

There is an edge directed from each message node \(m(L)\) to the aggregation node \(a(L)\). For example, there are edges from \(m[2, 3, 1]\) to \(a[2, 3, 1]\), and from \(m[2, 1]\) to \(a[2, 1]\), and from \(m[1]\) to \(a[1]\).Output of Aggregating Nodes

The output of an aggregation node is the majority of its inputs. For example:\( a[2, 1] = \textrm{majority}(m[2, 1], a[2, 3, 1], a[2, 4, 1], \ldots, a[2, 6, 1]) \)

If there are an equal number of attack and retreat inputs, then the majority value is defined to be any default value.

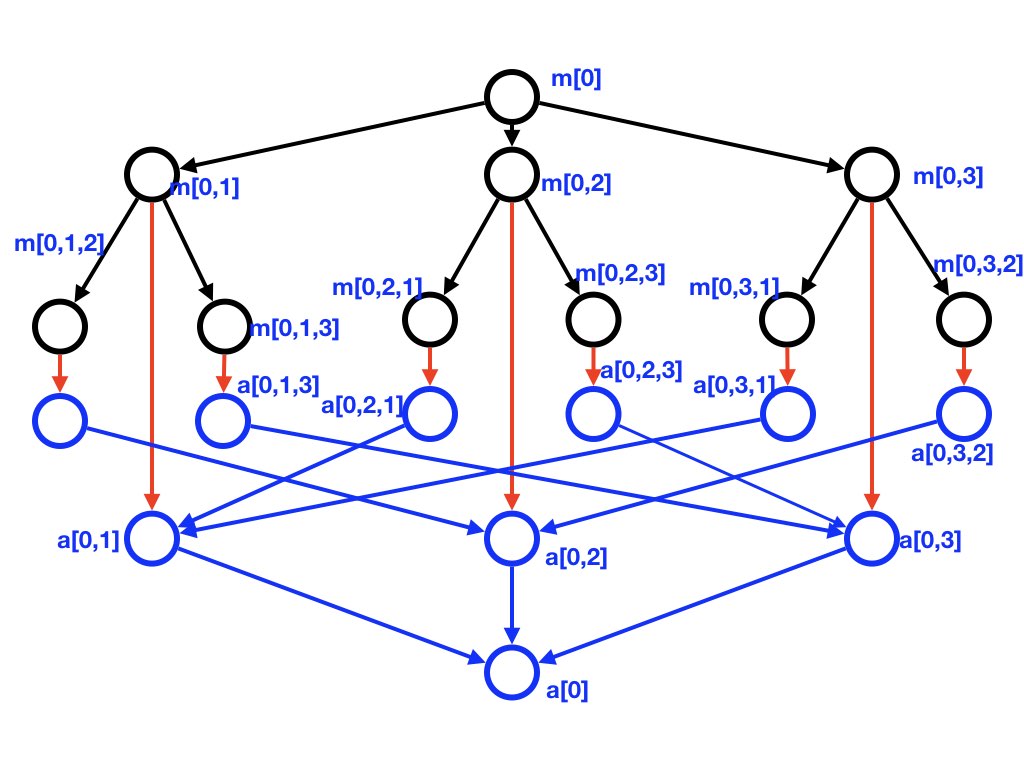

Example

The next diagram shows the data flow -- messaging and aggregation trees, and the connections between them -- for a system where \(N=4, t=1\).

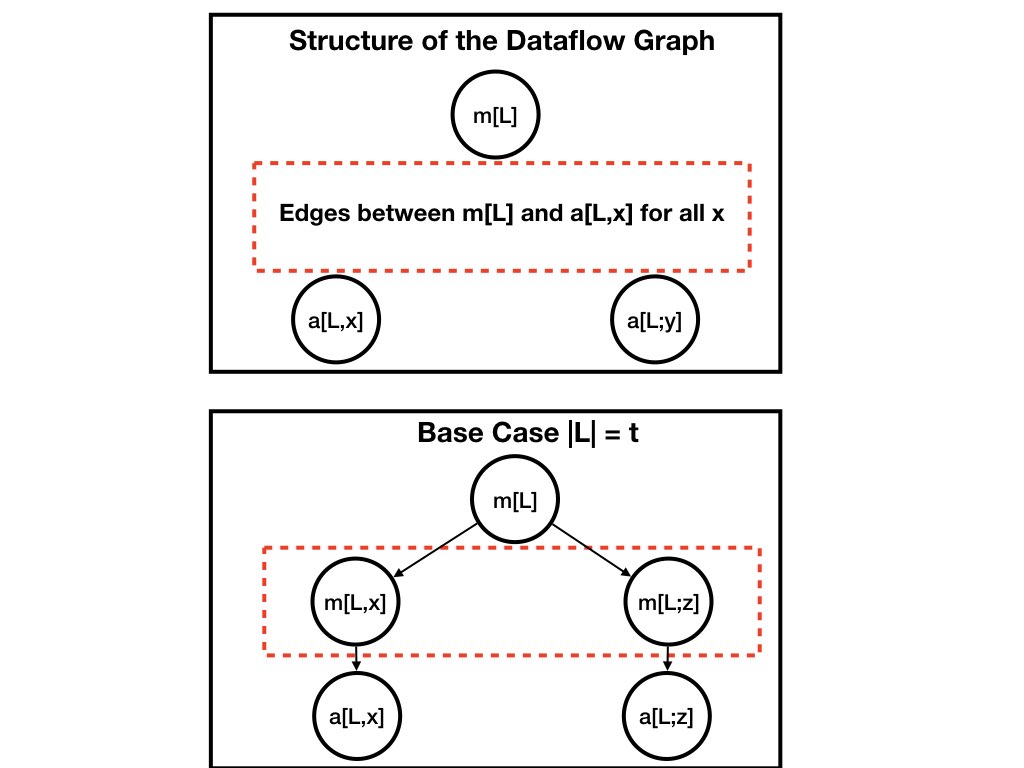

Inductive Generation of the Data Flow

The basic unit of data flow, which is replicated many times, is shown in the top diagram of the figure below. The input to the unit is a node \(m[L]\) of the message tree; this unit is specified by \(L\),and the message \(m[L]\). The output of the unit are nodes \(a[L, x]\) of the aggregation tree, for all lieutenants \(x\) not in \(L\).

The base case of the induction is a node at depth \(t\).

The input for the base case is \(m[L]\) where \(L\) is a list starting

with \(0\) and followed by \(t\) lieutenants.

For the base case, \(a[L, x] = m[L, x]\) for all \(x\).

The base case is illustrated in the lower diagram.

The value of an aggregation node is the majority of its inputs.

\( a[L,i] = \textrm{majority}(m[L,i], [\forall x \notin [L, i]: a[L, x, i]]) \)

For example,

\( a[0, 1, 2] = \textrm{majority}(m[0,1,2], a[0, 1, 3, 2], a[0, 1, 4, 2], a[0, 1, 5, 2], \ldots) \)

Proof of Validity

We prove that for all nodes \(m[L]\) of the message tree, if \(L_{*}\) is loyal then for all \(i\) not in \(L\):\( a[L, i] = m[L] \)

The proof is by induction. The base case is for message nodes at depth \(t\). We prove that if validity holds for message nodes at depth \(d > 0\) then it holds for message nodes at depth \(d-1\).

Base Case

See the lower diagram of figure 5. For a message node \(m[L]\) at depth \(t\),\( a[L, i] = m[L, i] \)

If \(L_{*}\) is loyal then \(m[L, i] = m[L]\). and the result follows.

Inductive Step

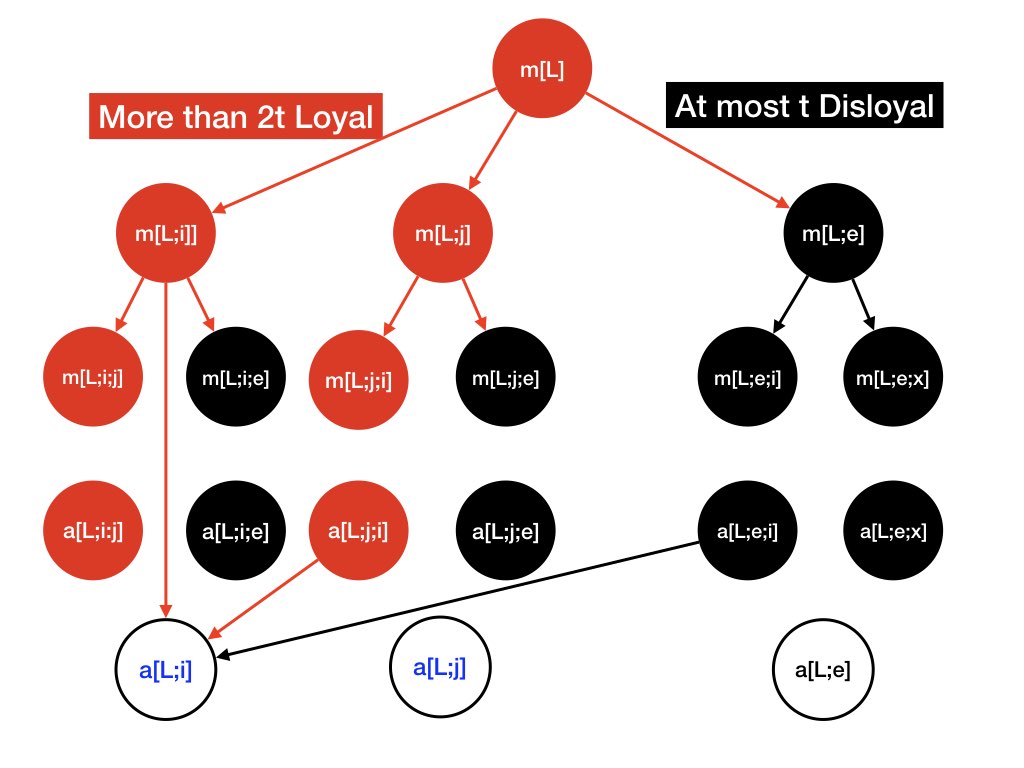

See figure 6.

A node \(L\) at depth \(d\) consists of \(d+1\) agents. Therefore, there are at least \(3t+1 - (d+1)\) lieutenants that are not in \(L\). Because \(d \leq t\) there are at least \(2t\) not in \(L\). So, at least \(t\) lieutenants not in \(L\) are loyal and at most \(t\) of them are disloyal.

Because \(L_{*}\) is loyal, \(m[L,i] = m[L]\).

By the induction assumption, for each loyal lieutenant \(j\) not in \(L\), and for each loyal lieutenant \(i\) not in \([L, j]\): \( a[L, j, i] = m[L, i] = m[L] \)

\( a[L, i] = \textrm{majority}(m[L,i], [\forall j \notin [L, i]: a[L, j, i]]) \)

The majority is taken over at least \(t + 1\) values equal to \(m[L]\), and at most \(t\) values that are different from it. And therefore \(a[L, i] = m[L]\)

Example

The next illustrates the proof of validity. Message \(m[L]\) is shown in red, and the flow of correct messages is shown in red edges and red nodes. For example, nodes \(m[L, i], m[L, j], m[L, i, j], m[L, j, i]\) are red because agents \(i, j\) are loyal.

A disloyal agent is represented by the symbol \(e\).

The output of a disloyal agent is unknown and is shown in black.

Node \(a[l. i]\) gets more than \(2t\) red inputs and at most \(t\)

black inputs, and hence the majority of its inputs is red.

Proof of Consensus

We will prove consensus for nodes at depth \(d\) if the number of faulty nodes is at most \(t-d\).Base Case \(d = t\)

In this case there are no disloyal lieutenants. For each \(i, j\), \(m[L,i]\) and \(m[L,j]\) are arbitrary; however \(m[L, i] = m[L, j]\).\(a[L, i, j] = m[L, i]\) and \(a[L, j, i] = m[L, j]\). Therefore the inputs to \(a[L,i]\) and to \(a[L,j]\) are identical and the result follows.

Inductive Step \(d < t\)

If the general is loyal, then consensus follows from validity.There are at most \(t - d\) faulty nodes. If the general is disloyal then there at most \(t-d-1 = t -(d+1)\) disloyal lieutenants. Therefore, the induction assumption holds for \(m[L, x]\). Therefore \(a[L, i, k] = a[L, i, j]\)

K. Mani Chandy, Emeritus Simon Ramo Professor, California Institute of Technology